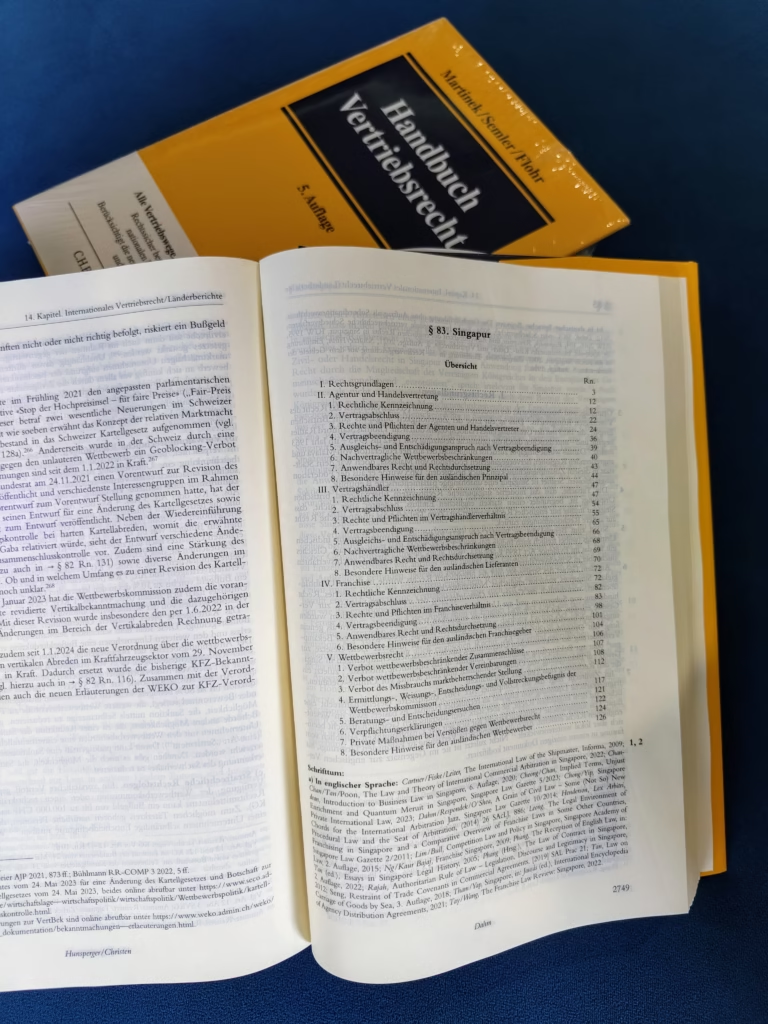

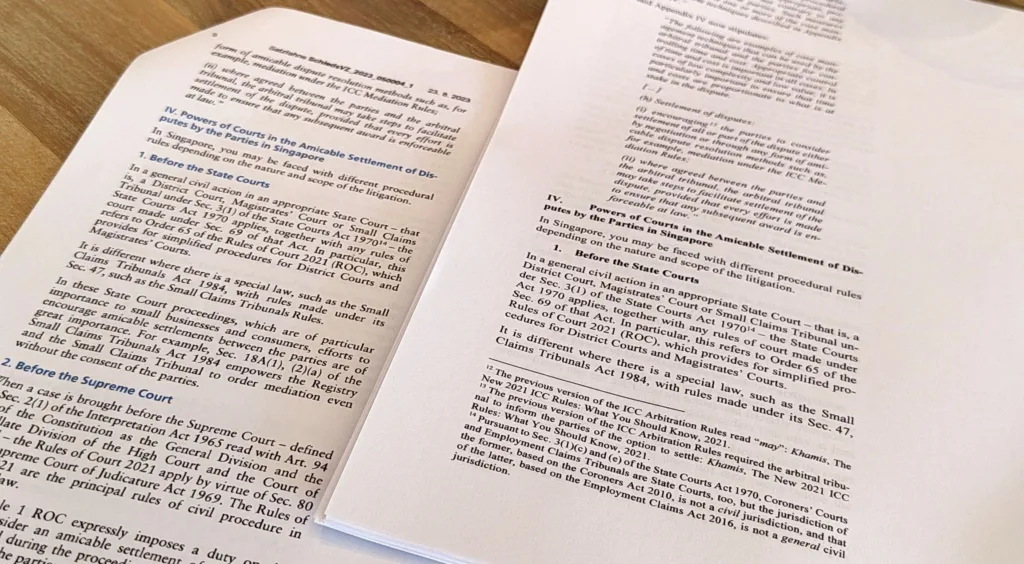

Hear ye, hear ye! The fifth edition of Handbuch Vertriebsrecht (Handbook of Distribution Law), edited by Martinek, Semler and Flohr, has been published. It’s a tome of 3,155 (plus LXXVII) pages that once again provides a systematic and detailed presentation of this area of law, both nationally (from a German perspective) and internationally. One of the new additions from my pen is a chapter on Singapore, which deals comprehensively with its commercial agency, authorised dealer, franchise and competition laws.